In Depth: The ‘People’s War’ Against the Epidemic in 16 Cities Across Hubei

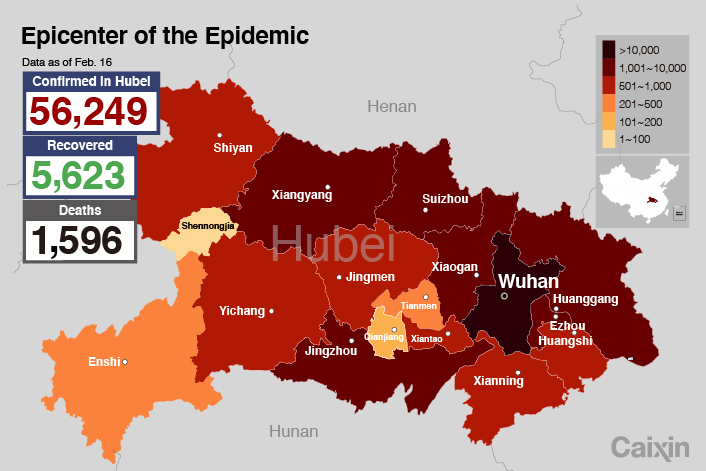

More than two months after the deadly coronavirus outbreak erupted in Wuhan, thousands of additional people continue to be infected every day in the now locked-down central Chinese metropolis and adjacent cities in Hubei province.

Tens of thousands of infected people have limited or no access to medical care. Hospitals are running short of medical supplies. Medical workers are exhausted and becoming infected themselves. All in all, what President Xi Jinping is calling the “people’s war” against the virus now known as Covid-19 is still struggling at the outbreak’s epicenter in Hubei.

At the same time, the number of new confirmed cases in the rest of China is showing signs of declining, suggesting the spread of the epidemic might be slowing. Most of China’s 1.4 billion population were told to stay home during an extended Lunar New Year holiday, and many factories and other businesses continue delaying resumption of commercial activity.

More than 25,000 doctors and nurses from all over the country have been dispatched to Hubei. More than 56,000 people in the province have been infected, accounting for more than 80% of the country’s total of confirmed cases. This means that if the battle in Hubei doesn’t end soon, other provinces could face depletion of medical resources.

Caixin reporters visited 16 cities in the province and spoke with officials at epidemic prevention offices, medical workers, patients, community staff, businessmen and local residents to sketch out a panoramic picture of the front lines. Painful lessons from some local governments and effective measures by others may prove valuable for decision-makers in working out next-phrase battle plans.

Defective system

A close-up of the 16 cities reveals a public health system not equipped to address a severe crisis such as this one, with slow responses from top to bottom. Medical workers, epidemic prevention experts and others cite shortages of health-care workers, lack of knowledge of epidemics, uneven medical resources, inconsistent control and prevention policies, chaotic management of emergency response, and sometimes health officials with no relevant experience.

One frontline doctor blamed public health leaders for lacking professional knowledge of epidemics. The health chief of Huanggang was unable to answer basic questions about the outbreak when interviewed on state television. Tang Zhihong was dismissed as head of the Huanggang Health Commission Jan. 30. Later, the Hubei provincial health commission’s party leader Zhang Jin and director Liu Yingzi were also dismissed. Tang and Liu didn’t have any public health-related experience.

Read more

Caixin’s coverage of the new coronavirus

The unreadiness of Hubei cities outside Wuhan also reflected uneven economic development in the province. As the capital of Hubei, Wuhan had GDP of 1.48 trillion yuan ($288 billion) in 2018, more than triple that of the second-largest city in the province.

This results in a wide gap in public health resources. As of the end of 2018, Wuhan had 3.42 doctors for each 1,000 residents, while in Xiaogan, the city with the second-most confirmed cases after Wuhan, there were fewer than two doctors for every 1,000 people.

The rest of China faces the same problem. Medical resources are concentrated in big cities. Small and medium-sized cities have long struggled with shortages of medical facilities and workers. This has forced patients from all over the country to travel long distances to seek treatment in big cities. Even within the same city, hospitals of various sizes have huge gaps in capabilities.

Public health and epidemic prevention are a lagging area or even a “blind spot” in China’s economic structural reform, said Huang Qifan, vice chairman of the financial and economic affairs committee of the National People’s Congress. China is incapable of dealing with a major epidemic like the current one because of a significantly underdeveloped public health system in terms of personnel, technology and equipment, the former mayor of Chongqing wrote in a recent article.

Slow response

From the time the first patient was reported in Wuhan on the last day of 2019 to an increase of nearly 15,000 new patients across the province in just one day on Feb. 13, the rapid spread of the epidemic caught everyone off guard.

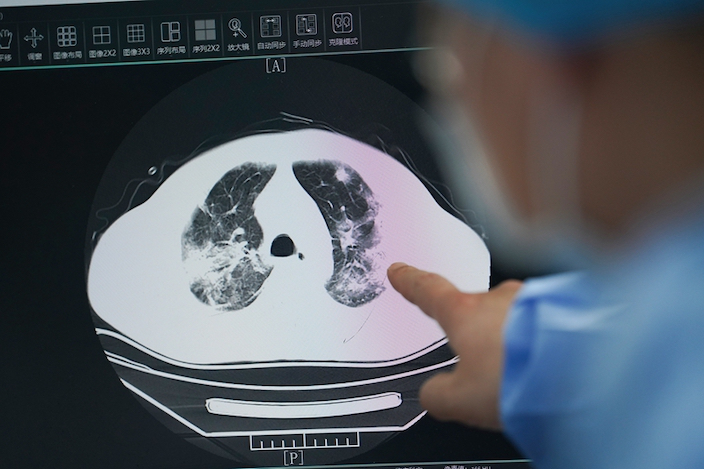

A change in guidelines that allowed chest X-rays to be used for diagnosis alongside standard lab tests resulted in Hubei’s one-day jump of 14,840 cases. Of those, 13,332 were confirmed via X-rays. Before the change in criteria, the number of confirmed cases rose by a couple of thousand a day over the previous two weeks.

|

Revised diagnostic guidelines made the number of new confirmed cases surge nearly 15,000 in a single day. Photo: Caixin |

The condition of more than 8,000 of Hubei’s 56,249 patients is severe, and almost 2,000 are in critical condition, the Hubei Health Commission said.

The Wuhan government’s slow response in the early stages of the outbreak is broadly blamed for the disease’s quick spread from Wuhan across China and to 25 other countries. The government issued an alert about cases of viral pneumonia of unknown cause Dec. 31, almost a month after the first patient was treated for the coronavirus at a Wuhan hospital Dec. 1, according to a study published by The Lancet medical journal.

In the following 20 days as more than 100 cases were confirmed, statements from the government and healthcare officials edged up from “no obvious evidence of human-to-human transmission” and “an outbreak under control” to “possible limited human-to-human transmission” and “low risk of sustained human-to-human transmission.” The Wuhan government didn’t drop the words “low risk” from official updates until Jan. 20, when Zhong Nanshan, a respiratory expert who discovered the SARS coronavirus in 2003, confirmed that the new virus was spreading from human to human, and 136 new cases were confirmed in two days.

Even as the epidemic was quickly developing, Hubei went ahead Jan. 11-17 with the so-called “two sessions” – annual gatherings of the people’s congresses and political consultative conferences at the provincial and city levels. On Jan. 18, Wuhan leaders hosted a community potluck dinner for 40,000 households.

This business-as-usual approach directly resulted in large numbers of patients swamping unprepared hospitals in Wuhan and nearby cities. Huanggang, a city just 50 miles east of Wuhan with a population of 7.4 million, is among the areas hit hardest by the epidemic, with the second- highest number of deaths after Wuhan and the third-highest number of confirmed case in Hubei.

A doctor at a Huanggang hospital told Caixin that the first suspected patient was recorded Jan. 3, and the hospital maxed out its capacity within two weeks. Doctors inexperienced in dealing with such an epidemic persisted in treating the sick as if they had a conventional flu.

Under-informed medical workers were also some of the first victims of the virus. On Jan. 7, a doctor and 13 nurses were infected at Union Hospital, affiliated with Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan. On Jan. 20, another 14 medical workers were infected at Shayang County Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, a small hospital three hours away from Wuhan.

More than 1,700 medical workers nationwide have fallen ill from the disease, with almost 90% of those in Hubei, Chinese National Health Commission deputy chief Zeng Yixin said at a press conference Friday. Six have died, including Li Wenliang, the doctor who sounded an early alarm about the human spread of the new virus before the information was made public and was punished by authorities for doing so.

Read more on the whistlebolowers:

Q&A: Whistleblower Doctor Who Died Fighting Coronavirus Only Wanted People to ‘Know the Truth’

More Wuhan Doctors Say They Faced Official Backlash Over Virus Warnings

Friday was the first time China released an official count of the number of infections among medical workers as such information is sensitive and could result in public panic. The official number doesn’t include suspected cases among medical workers.

In Yichang, Hubei’s second-largest city by GDP after Wuhan, about 10 medical workers have been infected, most of whom have not been confirmed, Caixin learned. Most of the infected are nurses, and the exact number has not been made public, probably to avoid causing panic in hospitals, a nurse at a Yichang hospital told Caixin.

Even after frontline doctors realized the gravity of the disease, hospitals found their hands tied in the absence of unified epidemic prevention guidance from the government. Some rural hospitals didn’t receive an overall deployment plan from municipal governments until Jan. 23, when the central government imposed a lockdown of Wuhan and other cities in Hubei to seal off the epicenter of the outbreak. Government healthcare officials in Huanggang didn’t discuss the epidemic with hospitals until Jan. 24.

Most medical workers become infected for lack of protection. The surge in patients left hospitals little time to convert regular wards into quarantine wards, and converted wards don’t meet medical standards for sanitation and layout. Substandard protective gear also leaves medical workers exposed to infection. The Yichang nurse said she could feel air leaking when wearing N95 masks that are supposed to be completely sealed.

Under pressure to identify every suspected case of infection, community workers were sent to conduct house-to-house temperature checks. Lack of protective gear put such workers at risk. Zhang Ju (a pseudonym), a community worker in charge of a community of more than 10,000 people in Ezhou, said her job included delivering groceries and providing sterilization to highly suspected households. The workers, mostly women, had to perform this work with no more protection than shower caps and aprons, she said. As far as she knows, several workers have been infected.

A Rare Bright Spot

In the fight against the fast-spreading virus, responses of just a few days faster can make a big difference.

|

Hubei province has more than 80% of the country’s total confirmed Covid-19 cases. Photo: Caixin |

On this map of Hubei, Qianjiang and Shennongjia are the areas with the fewest confirmed cases. It’s not surprising that Shennongjia, a remote mountain region with the smallest population in Hubei, has only 10 cases. But Qianjiang, a densely populated city on a convenient transportation route only 90 miles from Wuhan, had an extremely low total of 166 confirmed cases as of Sunday.

The relative success of Qianjiang is attributed to the city leader’s quick reaction in the early stages of the outbreak.

Upon first hearing of the virus while attending the “two sessions” in Wuhan in mid-January, the city’s Party Secretary Wu Zuyun Jan. 17 immediately ordered quarantines for the first 32 suspected patients.

“The mayor and I had a feeling this could be huge,” Wu said. “So we took preemptive actions, even if that could mean taking some risks not in accordance to rules.”

Wu didn’t elaborate on the “risks not in accordance to rules.” But such preemptive actions would likely have both economic and social costs. Accordingly, if the disease had turned out to be a false alarm, the decision maker would have to take responsibility.

A close study of the official Qianjiang newspaper didn’t show any mention of the disease until Jan. 23, indicating that Wu made a careful decision to take action without waiting for orders from above, and to do that quietly.

Hu Yue, Wu Hongyuran, Zhang Jin, Zhou Tailai, Huang Yanhao and Chen Lijin contributed to this report.

Contact reporter Denise Jia (huijuanjia@caixin.com) and editor Bob Simison (bobsimison@caixin.com)

- GALLERY

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR