Beijing battles ‘crisis of Chernobyl proportions’ in coronavirus outbreak

- Public fury is growing, with calls for more freedom of speech, but observers don’t expect any dramatic changes

- Xi Jinping has been mostly absent from view, as heads start to roll in Hubei province

Right in the centre of China, the city of Wuhan in Hubei province has also been at the heart of some key political events in the country’s modern history.

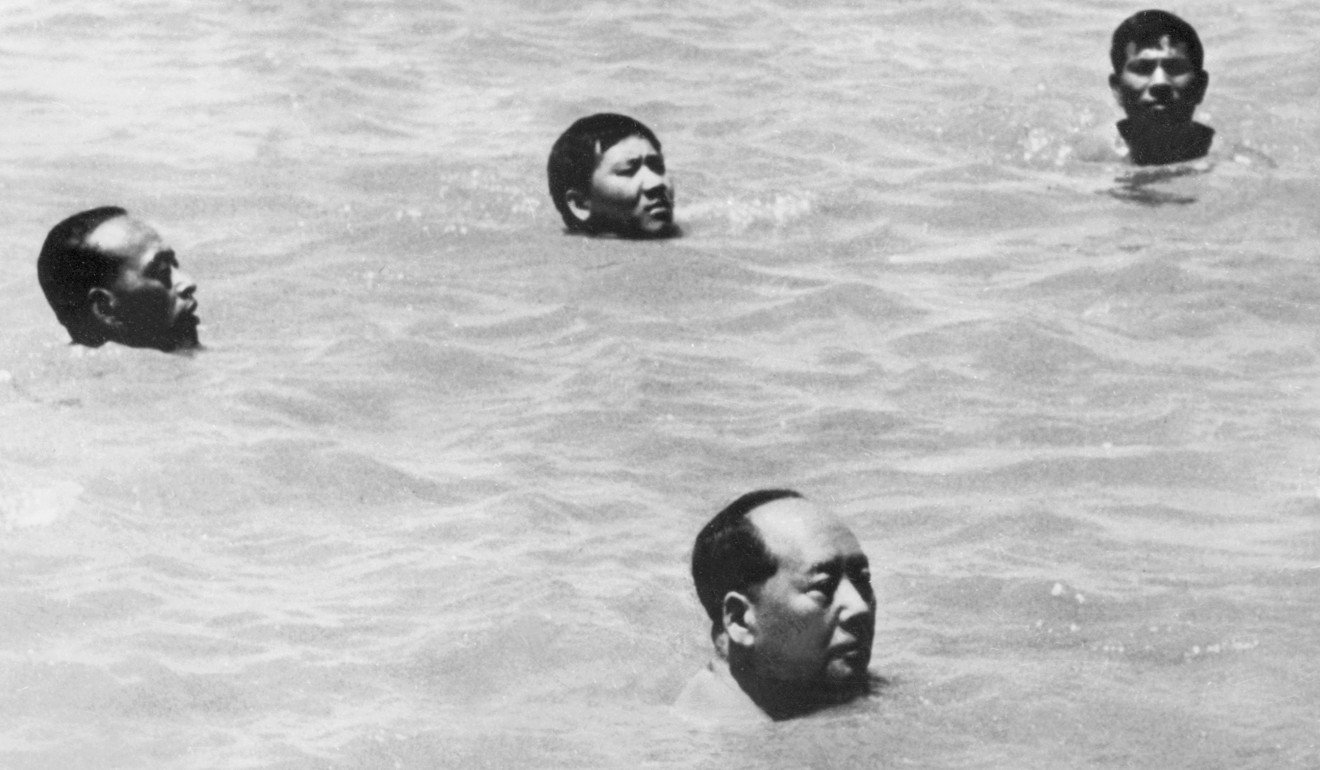

It was where a nationalist revolution began in 1911 that overthrew the Qing dynasty, ending thousands of years of imperial rule. And from where supreme leader Mao Zedong famously swam across the Yangtze River in 1966 at the age of 72, as he launched the Cultural Revolution – a decade of social and political turmoil which left wounds that remain unhealed.

The crisis has been referred to as “China’s Chernobyl” – the 1986 nuclear accident in the former Soviet Union that was worsened by an opaque system and incompetent crisis management – and is the worst the ruling Communist Party has seen since 1989. It is certainly the worst under strongman leader President Xi Jinping.

“This is clearly a crisis of enormous proportions,” said Dali Yang, a political scientist with the University of Chicago. “Failure … will be blamed on the system and especially on Xi, who’s staked out his personal leadership role.”

Yang said although the Chinese government’s propaganda machine was trying to spin the outbreak into a show of the country’s strength, it would not convince everyone.

“It will be a crisis of Chernobyl proportions, especially because we will have to contend with the virus for years to come,” Yang said. “Those who have sustained losses, in particular, will be asking questions, as has happened before in the aftermath of a crisis.”

While Beijing has tried to deflect blame for all those issues, claiming sabotage by foreign governments and organisations, it has not yet done so with the latest crisis. In fact, it has already shut down one conspiracy theorist, detaining an Inner Mongolian man for “spreading rumours” after he wrote on social media that the outbreak was the result of a biological war started by the US.

Tough questions

Zhao Suisheng, a political scientist at the University of Denver, said there was much less diversity of domestic public opinion about the causes of this crisis than for the trade war or the Hong Kong protests.

“Many Chinese sympathised with the government on the trade war, but the mainstream public opinion now is almost one-sided against the government,” said Zhao, who has written several books on Beijing’s control of information and public opinion. “This is something I haven’t seen since 1989.”

Zhao said the virus outbreak could see the party, and especially the Xi government, having to answer some tough questions.

“China’s political system under Xi – with its high concentration of power, its opaqueness, the overemphasis on ideology and Leninist discipline – has almost fully removed society’s capacity to handle such crisis,” he said.

Since Xi became the party chief in 2012, decision-making powers have been further concentrated at the top of the party, and sometimes with Xi alone. It has also been relentless in silencing dissenting voices within the party and across the country, clamping down more than ever on people expressing views online, and on civil society.

The outbreak of the potentially deadly disease, which is believed to have originated at a live animal and seafood market in December, has fuelled rare public discussions on the usually heavily censored Chinese internet. Some of the questions being raised online go right to the heart of the secretive party-state system, which Xi has fortified since he took power.

In part to calm the situation, Beijing sent a team of investigators with its anti-corruption body to Wuhan the morning after Li’s death to look into the case.

Where is Xi?

State media is also playing its part. Xi was shown on state television on Monday for the second time in two weeks, wearing a mask as he visited hospitals and community health facilities in Beijing. Sometimes it is more subtle. In January, state television reported that Xi had told World Health Organisation head Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus that he “personally directed” the response to the outbreak, but later in a Xinhua report the quote became “collectively directed”.

While Xi could be busy receiving information from the ground and coming up with a strategy to fight the outbreak, he could also be using layers of bureaucrats to protect himself from public anger, said Elizabeth Economy, director for Asia studies at the New-York based think tank Council on Foreign Relations.

“A less charitable view would be that he is creating multiple layers of plausible deniability for the poor handling of the crisis, including local officials, senior health officials and Premier Li Keqiang,” she said.

But she added that time was against the president as the situation dragged on.

“The longer the crisis endures, however, the greater the likelihood that the long-term credibility of the Xi government will be negatively affected more broadly within Chinese society,” Economy said.

An open letter from a group of Tsinghua University alumni has also called for a return to collective leadership.

But Zhao from the University of Denver said despite all this, it did not amount to a legitimacy crisis for Beijing. “As long as the economic growth does not see a steep fall, it’s still a key pillar for the party’s legitimacy,” Zhao said. “There’s also overreactions from other countries, including a level of racism abroad, that could be fed into the party’s nationalistic narrative.”

Xi has publicly acknowledged the magnitude of the political challenge posed by the outbreak. During last week’s Politburo Standing Committee meeting, it was called a “major test” of the governance system. “We must review this experience and learn lessons,” according to the official statement from the meeting, which confined those “lessons” to the technical level.

Economy from the Council of Foreign Relations did not expect any major shift in areas like freedom of speech. “I don’t see any evidence that Xi is planning to change course and recognise the value of a larger voice for civil society as a result of this crisis,” she said. “Xi has already suggested that the lessons learned are the need for a better crisis management system and the closure of the wet markets. There is no mention of more openness for independent voices.”

Beijing pins hopes on ‘guy with emperor’s sword’ to restore order in coronavirus-hit Hubei

Chen Daoyin, an independent political scientist and a former Shanghai-based professor, said more structural change in Chinese politics was impossible without strong dissent from within the party.

“The Chinese culture is one that only blames local officials but never the emperor. There are already people cheering for Beijing as it sent investigators to Wuhan,” Chen said. “And within the party, there’s no one with the guts or capacity to challenge [Xi] yet.”

Zhao said Xi might give some thought to choosing a successor, but his priority was to remain powerful.

“He must always be bearing in mind Mao’s lesson of picking successors but ditching them one by one,” he said. “[But Xi’s] worst fear is being treated as a lame duck early on, so there won’t be any serious selection of a successor before his third term.”

Purchase the China AI Report 2020 brought to you by SCMP Research and enjoy a 20% discount (original price US$400). This 60-page all new intelligence report gives you first-hand insights and analysis into the latest industry developments and intelligence about China AI. Get exclusive access to our webinars for continuous learning, and interact with China AI executives in live Q&A. Offer valid until 31 March 2020.