In Depth: China’s Local Governments Find It Hard to Make Ends Meet

Local governments across China might find it hard to make ends meet this year, as coffers already straining amid slowing growth and tax cuts are put under extra pressure by the coronavirus outbreak.

China missed its fiscal revenue growth target last year, with growth falling to its slowest pace for over 30 years. Both the central and local governments saw revenue growth decline from the previous year.

Many provincial-level governments have set their fiscal revenue growth targets for 2020 lower than those for last year. However, they are likely to have to spend more to both fight against the coronavirus epidemic and mitigate its economic impact. As of Sunday, the outbreak had killed over 2,900 people in the country and left many businesses with a liquidity crisis.

In response, Beijing is allowing local governments to sell more bonds earlier than usual to fund investment. Economists have suggested that policymakers will allow the country’s fiscal deficit to rise past 3% of GDP, long seen as a key psychological threshold. However, as revenue sources are limited and local governments are still under strict orders to prevent and defuse debt risks, the task ahead will not be easy.

A tough 2019

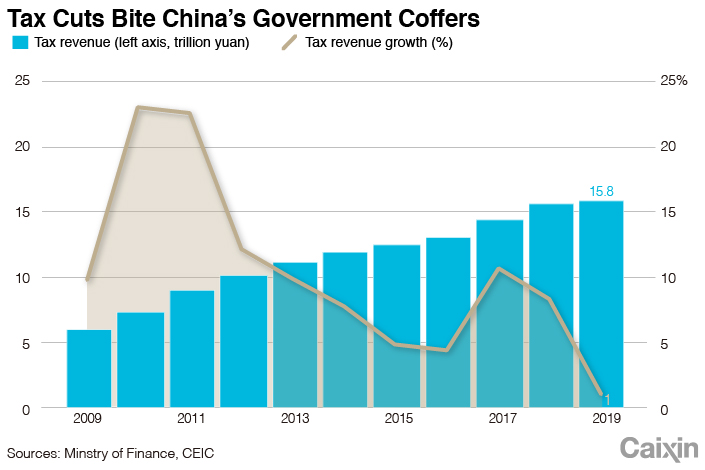

The size of the tax and fee cuts enacted over the past two years have exceeded the expectations of some officials. Last year, the state reduced tax and fee burdens by over 2.3 trillion yuan ($329.8 billion), accounting for over 2% of GDP, according to estimates (link in Chinese) by the Ministry of Finance.

The government cut income tax and value-added tax (VAT), as well as other taxes, and reduced the premiums firms must pay toward their employees’ pensions.

|

Tax and fee cuts likely boosted last year’s GDP growth by 0.8 percentage points, but have put significant pressure on fiscal revenue in some places, Finance Minister Liu Kun said in December. Last year, total tax revenues for governments at all levels only rose by 1%, down 7.3 percentage points from 2018.

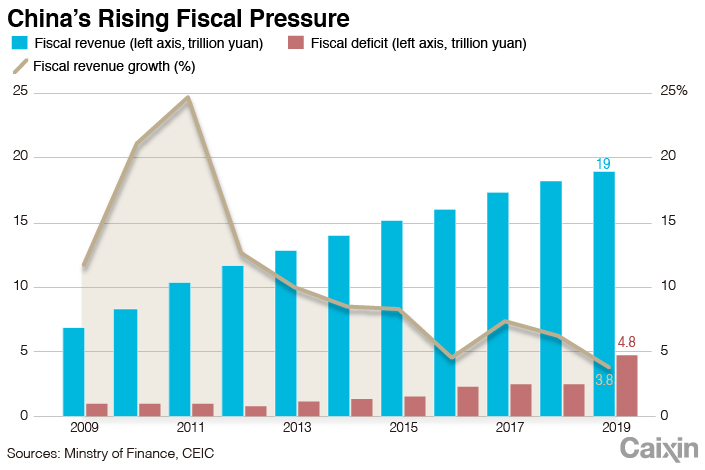

Total fiscal revenue grew 3.8% to 19 trillion yuan last year, official data show, missing the 5% growth target. That was 2.4 percentage points lower than growth in 2018 and the slowest rate since 1987. Local governments’ revenue growth of 3.2% was slower than that of the central government, which came in at 4.5%.

|

Of the 30 provincial-level regions on the Chinese mainland that have announced their fiscal revenue for 2019, 24 saw slower growth compared with the previous year, while revenue in Heilongjiang and Jilin provinces, Chongqing municipality and the Tibet autonomous region actually dropped from the year before.

Local governments have resorted to other revenue sources, including selling state-owned assets, and creaming off more profits from state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The country’s nontax revenue last year jumped by 20.2% to 3.2 trillion yuan, up from a 4.7% decline in 2018. However, these measures cannot replace tax in the long run, as measures like selling assets are one-time only, observers say.

A tougher 2020

Local governments are generally not optimistic about their fiscal situation in 2020. Of the 29 provincial-level regions which have released fiscal revenue targets, 22 of them set lower growth targets than last year.

Beijing and Shanghai, two of China’s richest cities, expect to see zero growth in government revenue. Jilin and the Inner Mongolia autonomous region said their revenue will likely fall this year. Multiple governments cited downward pressure on economic growth and tax and fee cuts as factors.

However, these targets were mostly made before the scale of the coronavirus outbreak became clear. Zhang Yu, chief macroeconomic analyst at Huachuang Securities Co. Ltd., said the epidemic would make even the lower fiscal revenue targets hard to meet, and some might need to be revised.

Some poorer regions that rely on central government financial aid also worry that Beijing will not be as generous as before due to the impact of tax and fee cuts. “It is unprecedentedly difficult (this year) to win subsidies from the central government,” said the 2020 budget report (link in Chinese) of Northwest China’s Qinghai province.

Despite this, regions will have to boost spending to both fight against the epidemic and aid businesses impacted by it. Finance authorities across the country have allocated over 100 billion yuan (link in Chinese) to fund this fight, including offering subsidies to patients and medical staff, according to the finance ministry. The state is temporarily exempting or cutting (link in Chinese) firms’ contributions to employees’ pension, unemployment and work injury compensation insurance funds, which is expected to ease the burden (link in Chinese) on Chinese firms by some 600 billion yuan.

Ways out

As far as there is a solution to this problem, it will come on two fronts: broadening income sources and reducing expenditures.

To save cash, multiple local governments have vowed to cut their daily spending, including Beijing (link in Chinese).

The central government so far has given the green light for local governments to issue 1.85 trillion yuan of bonds in two rounds of early allocations of 2020 debt quotas, up from 1.39 trillion yuan of early allocated quotas for 2019. Annual debt quotas were originally issued after approval by the National People’s Congress at its annual session in March, but the legislature’s standing committee passed a bill in 2018 allowing the Ministry of Finance to assign part of the quotas early in an effort to push more spending into the first quarter of each year and help local governments better plan their budgets.

However, if local governments want to raise money beyond bond quotas, their hands are somewhat tied as regulators have instructed them to prevent and defuse hidden-debt risks. Hidden debts are off-balance-sheet. They are generally borrowed by local government departments and SOEs including financing vehicles, and guaranteed or repaid by local governments. Economists estimate that local governments’ off-balance-sheet debts far outweigh those actually on their balance sheets.

Economists have suggested that the central government raise the fiscal deficit target. A group of economists said in a report (link in Chinese) last month that the target could be raised to 3.5% of GDP, which would add 700 billion yuan more to spend. The Chinese government has been reluctant to see its deficit-to-GDP ratio rise above 3%, seeing that level as a red line that would increase fiscal risks, researchers say. China’s budget deficit target for 2019 was 2.76 trillion yuan, or around 2.8% of GDP, up from 2.6% in 2018.

Contact reporter Guo Yingzhe (yingzheguo@caixin.com) and editor Joshua Dummer (joshuadummer@caixin.com)

Caixin Global has launched Caixin CEIC Mobile, the mobile-only version of its world-class macroeconomic data platform.

If you’re using the Caixin app, please click here. If you haven’t downloaded the app, please click here.

- 1In Depth: Why China’s Project Whitelists Can’t Cure Real Estate Slump

- 2Chart of the Day: China’s Nuclear Power Investment Hits New High

- 3In Depth: Chinese Education Firms Learn Tough Lessons Overseas

- 4Cover Story: China’s Balancing Act to Keep Its Social Security System Afloat

- 5China’s Youth Struggle to Find Work Despite Drop in Jobless Rate

- 1Power To The People: Pintec Serves A Booming Consumer Class

- 2Largest hotel group in Europe accepts UnionPay

- 3UnionPay mobile QuickPass debuts in Hong Kong

- 4UnionPay International launches premium catering privilege U Dining Collection

- 5UnionPay International’s U Plan has covered over 1600 stores overseas